Via del Pratello

Pratello (in current italian means ‘little lawn’).

Peratello. Peradello. Peradel. Pradel (in Bolognese dialect means little pears field).

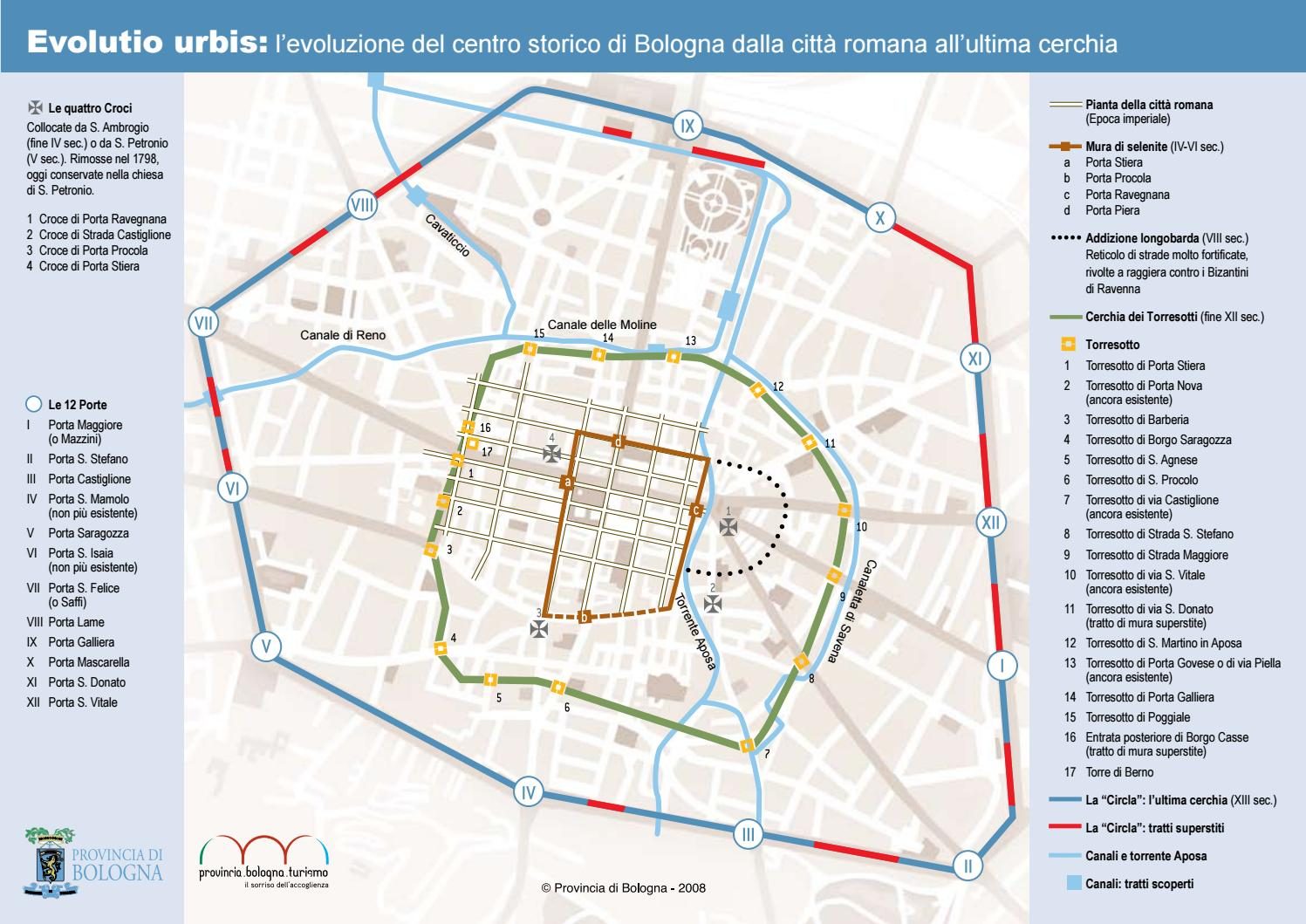

While the current diction of the name does not coincide with its actual root, it is not misleading concerning how this street origin and history. After a period of thriving under the Roman Empire, the street has been repeatedly physically excluded from the rest of the city, determining its rural-urban in-betweenness. In fact, throughout the middle-age, it was for the most part a peri-urban conglomerate of houses and pear fields whose development was not planned by the city’s regency. Furthermore, not being protected by the city’s walls, exposed the area to the influx of all sorts of people and incursions from foreign armies and mobs. Historical accounts describe it as a neglected borough (civitas antiqua rupta) where social outcasts and poor people had a chance to earn a living either through hard work or crime. Thieves, scammers, fake beggars, sex workers lived together with farmers, craftsmen. For about a century, one of the main city’s canals ran through the street and, even after the waterway was diverted elsewhere, jobs that made us of the canal were frequent among the street’s population. Up until the half of the 20th century – before the canal was rendered underground – washerwomen (lavandaie) kept on washing clothes in it, as a monument placed in the street’s vicinity reminds.

For about a century, one of the main city’s canals ran through the street and, even after the waterway was diverted elsewhere, jobs that made us of the canal were frequent among the street’s population. Up until the half of the 20th century – before the canal was rendered underground – washerwomen (lavandaie) kept on washing clothes in it, as a monument placed in the street’s vicinity reminds.

The street was considered inadequate for serving as a major access way to the city soon after its physical inclusion within the city’s walls, which occurred with the construction of so called third belt of walls (Circla) between the 14th and 15th century.

A trace of this can still be found in the outer side of the walls right at the end of Via del Pratello: the wall, which is today part of the San Rocco orthodox church, originally had a passage “door” (porta) that gave access to the city precisely through Via del Pratello. However this was closed less than a century later in favour of accesses throguh a larger and more orderly street close by.

To trace connections between the street’s popular and crumby character throughout the middle age to its 20th Century history would be presumptuous and difficult to achieve. However it is interesting to see how the narrative representations of the street in medieval and industrial times show some resonance. The several taverns that used to attract and host the variety of people that inhabited and frequented Via del Pratello in the Middle Age have been a peculiar feature of the street in the second half of the 1900 when it became a space of freedom for eccentric people, marginalized people and political militants. A fancier version of taverns, bars and restaurant are also a trademark of the current transformation of the street into the hangout of a slightly more commercial type of eccentric people: the hipsters.

Half way into Via del Pratello, the cross with Via Pietralata represents the geographical and social heart of the street. By simply standing in its middle for some 15 minutes all sorts of objects and symbols become visible and the immense stratification of histories and people of this street starts emanating from its walls and porches. What follows is an unsystematic – and intentionally disorderly – set of reflections starting from -and linking together – various photos I took from within the five squared metres of so called Crusél (‘little cross’)can give a sense of the multiplicity of stories and people that enliven Via del Pratello.

La Zanza and the painter

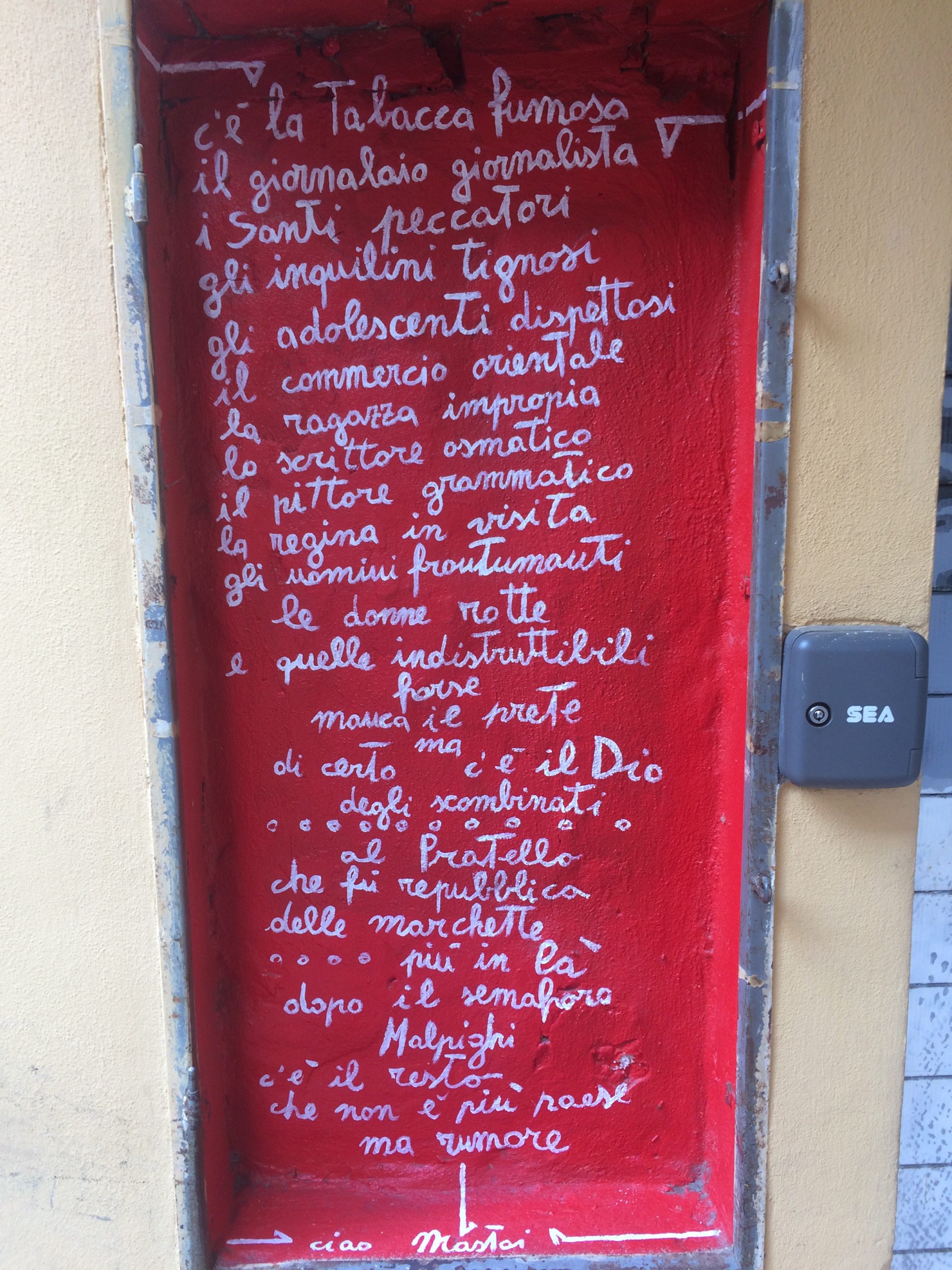

Few days ago I came across a serie of video in which people considered to be ‘characters’ (personaggi: particular people, eccentric or not, bearers of arts and or memories linked to a specific place or group of people) of Via del Pratello shared a couple of anecdotes about the street. One of the people featured in the serie, a lady called ‘La Zanza‘ (‘The Mosquito’), shares an anecdote about a tavern called Ghitòn where people could buy “15 minutes of beans” and eat from holes in the main counter with chain-locked spoons as many beans as they could for fifteen minutes. The following story she shares is about Roberto Mastai, a painter and illustrator who spent most of his life in Via del Pratello and decorated its walls and bars with his art. As an article that commemorates his passing says “he was adopted by Via del Pratello, or perhaps he had adopted it”. After his death in 2013, the residents of the street who knew him organized his funeral and the tranfer of his body to his hometown. Few months later, in collaboration with a local sreet artist, they placed a portrait of Mastai on the shutter of the tobacco shop on one of the Crusel ‘s corners. Next to it they placed a poem Mastai wrote that tries to capture and depict the soul of Via del Pratello.

La Zanza, who is sitting on the opposite side of the cross during the interview, takes the cameraman in front of the poem which she really wants to read out loud, even though her voice breaks in sobs after the first couple of verses:

“There is the smokey tobacconist, the newsagent (who is also a) journalist, the sinner Saint, the mulish tenants, the mischievous adolescents, the oriental trade, the inappropriate girl, the asthmatic painter, the visiting queen, the shattering men, the broken women and the indestructible ones. Perhaps the priest is missing but surely there is the God of the messed-ups.

“There is the smokey tobacconist, the newsagent (who is also a) journalist, the sinner Saint, the mulish tenants, the mischievous adolescents, the oriental trade, the inappropriate girl, the asthmatic painter, the visiting queen, the shattering men, the broken women and the indestructible ones. Perhaps the priest is missing but surely there is the God of the messed-ups.

(This goes) To Pratello, that was the republic of harlotry… further down after the Maplighi’s traffic light (cross after which the Pratello ends and the rest of the city center starts) there is the rest, which is no longer village but noise.”

The poem gives a sense of how the narration of the street as a lively, creative, damned and absurd one survived throughout centuries and still today affects people imagination and emotions in very substantial ways. The centrality of ‘characters’ emerges both from the poem and from the serie of videos: both of them portray people who have very intimate connections with the neighborhood to the point that one cannot exist without the other.

Lino: “the newsagent journalist”

On the opposite side of the road Lino Neri, the newsagent, leans bent over the shelves of his shopfront window, meticulously arranging magazines and newspapers. This has been his job for over 40 years and he is one of the first newsagent who had a library section in his shop. Every morning, before opening the shop he does door to door delivery of the newspapers. He is considered by many one of the main living sources of memory in the street in that he witnessed the history of the street since the times of Radio Alice (late ’70s) until today. He is one of the characters featured in the videos serie mentioned above: he tells a story about the Pratello’s squatted houses of the ’90s and the several concerts the were hold in their basement.

He is considered by many one of the main living sources of memory in the street in that he witnessed the history of the street since the times of Radio Alice (late ’70s) until today. He is one of the characters featured in the videos serie mentioned above: he tells a story about the Pratello’s squatted houses of the ’90s and the several concerts the were hold in their basement.

Other forms of memory: the Resistenza

Right above Lino’s shop, there is a memorial stone and a flowers crown dedicated to nine partisan soldiers (Partigiani) who died during the Liberazione (Liberation) struggles against nazi and fascist occupation of the Italy in the last years of World War 2. Bologna and its surroundings, historically communist areas, have been the Resistenza’s (Resistance) front line for about a couple of years, during which many people retreated on the mountains and engaged in guerrilla war. Memorial stones like the one in the photo,  as well as monuments that commemorate the fallen of Resistenza, are placed in many spots across the city. However, Via del Pratello, also due to its leftist connotation even after the end of WW2, still does a lot of activity to celebrate the soldiers who died for our freedom. A collective called Pratello R’esiste (Pratello R’e(x)sists) took the lead in coordinating the celebration of the 21st and 25th of April, days in which respectively Bologna and Italy were finally freed from the nazi-fascist army. A week of talks, readings, artistic performances, concerts and, in general social gathering are hosted by Via del Pratello. Symbols and flags are exposed from the windows and are placed on the street’s walls: the small label “restiamo umani” (Let’s stay human) underneath the stele was added during last year’s celebration. The red star hanging above the cross – see photo at the end of previous section- is also part of the installations related to the celebration of the Liberation by street committees and collectives. Through these symbols connections are created between WW2 partisan guerrilla, the ’70s political turmoil, the ’90s squatting period and current libertarian-leftist political ideals and struggles.

as well as monuments that commemorate the fallen of Resistenza, are placed in many spots across the city. However, Via del Pratello, also due to its leftist connotation even after the end of WW2, still does a lot of activity to celebrate the soldiers who died for our freedom. A collective called Pratello R’esiste (Pratello R’e(x)sists) took the lead in coordinating the celebration of the 21st and 25th of April, days in which respectively Bologna and Italy were finally freed from the nazi-fascist army. A week of talks, readings, artistic performances, concerts and, in general social gathering are hosted by Via del Pratello. Symbols and flags are exposed from the windows and are placed on the street’s walls: the small label “restiamo umani” (Let’s stay human) underneath the stele was added during last year’s celebration. The red star hanging above the cross – see photo at the end of previous section- is also part of the installations related to the celebration of the Liberation by street committees and collectives. Through these symbols connections are created between WW2 partisan guerrilla, the ’70s political turmoil, the ’90s squatting period and current libertarian-leftist political ideals and struggles.

More material types of connection

In the Crusél it is not only streets and people that cross each other but also electrical infrastructures. It is quite unusual to see bundles of cables running along outside walls as most of them are underground or inside the buildings’ walls. The Crusél, however, offers a glimpse of how dense the wiring of post industrial European cities can actually be.

The way the cables are laid down is telling of how different Via del Pratello is from the rest of the city. Invisibility of infrastructure is in fact a typical trait of what is conceived as an advanced and modern city. The illusion of emancipation from the materiality of infrastructures is part of contemporary middle-class pursued desires on urban aesthetics. It would not be surprising to find out that a wiring such as the one captured in these photos is perceived by most Bolognese people as ugly, dangerous and backward. In Via del Pratello, though, wires stand in such form and can be read as an unconscious reminder of the often spontaneous, informal and stratified development of the street’s built environment across ages.

These cables physically connect the neighborhood and its inhabitants, in that they are dependent on the same material infrastructure in order to have access to electricity, phone line, Wi-Fi. Services such as a house phone line that most people in European towns take for granted, were quite a luxury only a few decades ago. As the following photos witness, public telephones were situated in taverns and bars that hence also served as a public access point to the phone line. Some signs signaling the presence of public phones are still standing nowadays even though the service is no longer available.

In the video serie mentioned above a man called Trippo who defines himself as “a punker from the ’70s” tells the audience of when, in the early ’80s, he went to the bar located on the Crusél and the owner, who he barely knew, let him know that his family had called from his hometown to say his mom was ill and he had to go visit her. Since he could not afford the trip, the owner of the bar offered to take him home – a three hours drive- the day after and did so without asking for any compensation for the fuel and highway price.

The reflections I presented above moved from an observation of the city’s material forms as an archive to explore in order dig up fragments of the city’s history. In particular engaging Via del Pratello through such lens allowed be to take a glimpse of layers and bits of the street’s history and identity I was not aware of or I had never carefully focused on. What also emerged is the centrality of people both in the preservation of the street’s memory and in the making of its identity. In this sense, while I was conducting my research trying to look at “the city as archive” the expression “people as archive” kept popping up in my head throughout the whole process, in that it became quite clear how tightly interconnected the human and non-human components of the city are. This fully resonates with the strong sense of belonging that many of the characters I came across expressed in relation to Via del Pratello. The same sentiment was reported by one of them in describing the deep interconnection existing between the street’s painter. Interestingly, in the very first post of this blog I expressed a feeling that is very akin to the one described in the previous lines when I wrote that “This place is a part of me as much as I am a part of this place”.