I decided to carry out the countermapping exercise by taking inspiration from a very compelling passage found in one of the introductory contributions to the book “This is not an atlas“ by Kollektiv Orangotango+. In the conclusion of his chapter “Counter-Cartographies: Politics, Art and the Insurrection of Maps” André Mesquita tries to unpack the issue of map production in an overly mapped world and of how to make countermapping a truly emancipating practice instead of yet another tool of power to be used against oppressed people. As he goes:

Why then produce more maps in a mapped world? My response is that we need to make and remake maps not only in order to confront the forms of control but also so we can expose the underlying mechanisms. Most of all we need to produce counter-maps in order to create actions that might affect our perceptions of social space and its different vectors, to change our modes of looking at the world and create new dialogues and discoveries. […] A statement cited from an interview I did with the members of the Counter-Cartography Collective seems to summarize the spirit of this proposal in other words: “To map systems of oppression, not oppressed people!” (p. 26)

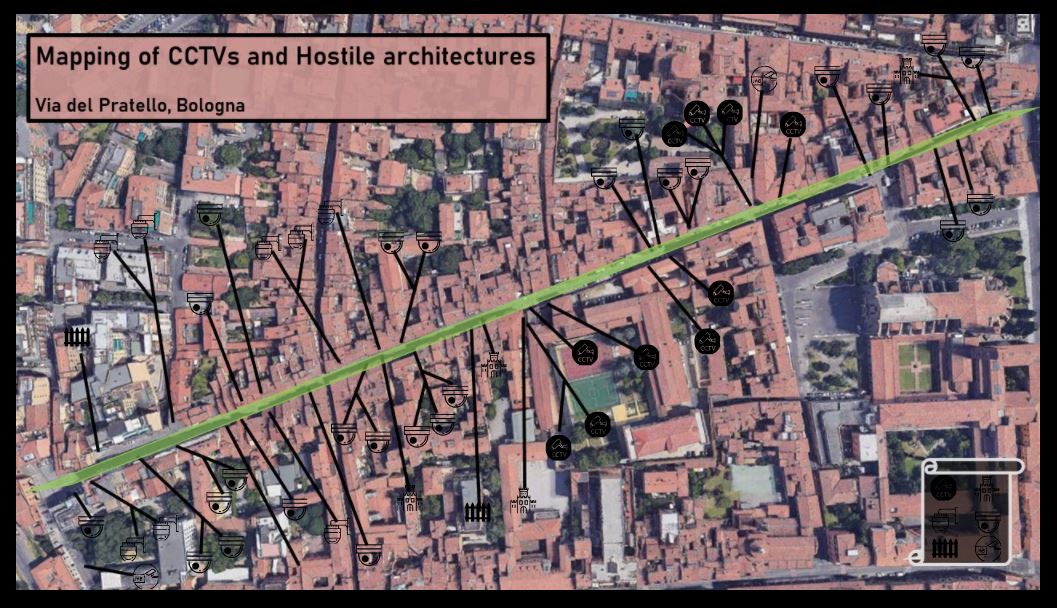

Trying to translate this powerful idea into the Pratello neighborhood, I decided to map out some of the tools and mechanism that contribute to create exclusionary geographies in the area: security cameras and so called hostile architecture, namely those architectural and design features that dissuade behaviors and exclude certain people from a place. Instead of trying to retrace and focusing on specific groups of people who are oppressed in this space or excluded from it, I decided to look at the systems that enable processes of exclusion and oppression. In fact, even though with varying intensity and in different ways, such mechanisms affect all the people who attend the Pratello neighborhood and it could be -and should be- of interest for anyone to gain awareness of them. Furthermore a map is a provisional tool that can be expanded and modified. In this sense the small experiment I carried out could represent a starting point to develop a larger mapping of the area through the lens of security and control.

[The full interactive map can be accessed on Thinglink by logging in with these credentials: useranme: maipi@guerrillamail.info ; Psw: forget me]

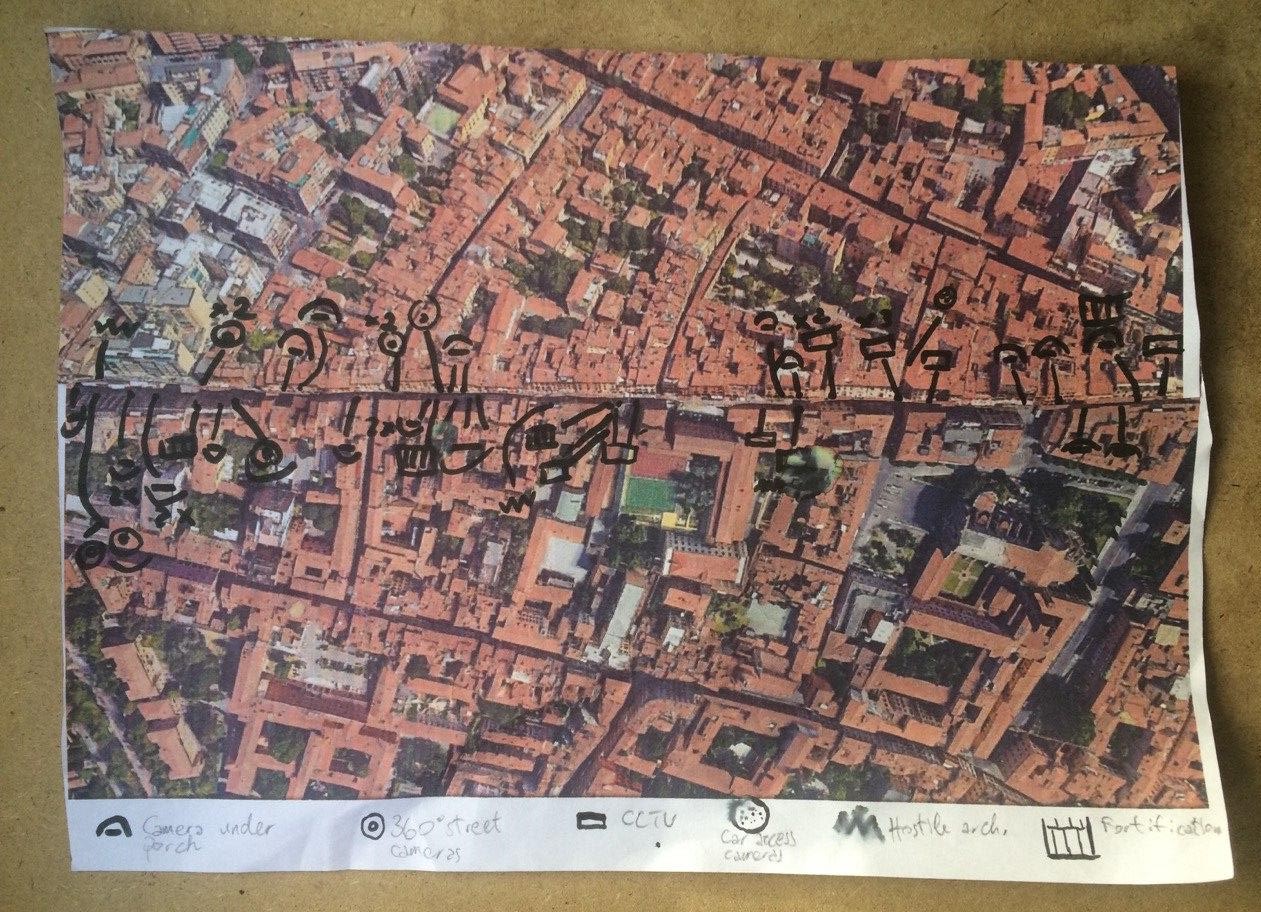

I realized the map by printing a satellite image of the area on an A4 paper sheet. With the company of a friend of mine -and fellow social researcher- I walked through Via del Pratello in search of security cameras and hostile architectural features and recording them on the map with a marker. As the legend on the map shows, I differentiated between the types of cameras as well as between the hostile designs.

Concerning CCTVs I grouped together all of those cameras that belong to private subjects such as residents and shop owners who make use of them to improve the security of their business and property. While these cameras are not directly aimed at exerting social control on those who frequent the area, they do capture portions of the public space in front of the private spaces they should protect. The recordings of such cameras can be accessed by the police up to 48 hours later in case any investigation requires footage from a specific spot. Furthermore, many of these cameras are located in quite dark corners under the street porches and are hardly visible. As a result, people happen to be constantly filmed, often without even being aware of it.

I then isolated cameras that are installed and controlled by the national police for the purpose of protecting, in this case, the local police station and the juvenile prison which are both located in Via del Pratello. These cameras capture quite broad areas in front of these two buildings and, due to the scarce width of the street, they end up capturing most of it and of its pedestrian traffic. Similar to these cameras there is a set of recently installed 360° degrees cameras that are controlled by the Municipal Police. They are located in strategic parts of the street where they can have the greatest visibility over the surrounding space. They played an important role in fighting petty crime, especially small size drug dealing in the area.

Finally, a smaller group of cameras serve the purpose of controlling the access of cars to the pedestrian area of Via del Pratello and are equipped with number plate recognition devices. While they are not meant to intercept deviant behaviors, they do function as a sort of video recording gate to some of the main accesses to the area.

Concerning hostile architectures, I have to say that the area does not abounds with this kind of urban features and tools. I retraced only a few which I divided into two groups: ‘fortifications’ are those urban elements that were added to preexisting structures in order to render them more solid and safe, whereas ‘hostile design’ refers to details and features of common urban elements (a bench, a door, a wall) that are conceived for dissuading specific behaviors (loitering, sleeping, ueeing, sitting, skating etc.). The latter tend to be more integrated into the urban landscape and make use of beauty and style to conceal their actual purpose, escaping more easily the sight of those who are not directly affected by them.

In the map I have only reported the most explicit ones and I did not expand my categorization to all of those tools that focus more on the exterior appearance of the urban space rather than on a specific function but that, by doing so, still have the effect of dissuading social practices and excluding people. While I was walking I was also wondering whether dehors (outside bars’ platforms with seats and a protective fence that clearly delineates the space of the bar) should also be considered as a form of hostile architecture in that not only they appropriate a portion fo the public street for commercial purposes, but they also create a clear distinction between those who can afford to sit at bars and those who cannot. Furthermore they make it more difficult for street vendors to walk through the tables and earn their living. This is an example of a further mapping that could be carried out in the area.

Carrying out the mapping did not simply lead to a visual representation of the control systems that are present in the area. It also made me walk through the space with a different and more observant approach, which gave me -and my walking partner- a new and perhaps deeper awareness of a place we often attend to. Interestingly, the friend who helped me doing the mapping, was initially skeptical about the high presence of cameras in the area and he thought I was simply carrying out an exercise to meet the requirements of an academic module. However, by the end of our walk he was surprised by the quantity of scarcely visible cameras we mapped.

Being repression and oppression increasingly enabled by technical and technological devices, it is is important to keep track of the distribution of such tools in the places we frequent and call home. This map tried to make a little step in such direction.